they rest in peace

far from the bustle of traffic, i stopped among the graves to consider: why did we pay our respects to the dead anyway? did they, by ceasing to be, achieve sanctity denied them when alive? or did they serve merely to remind us of our eventual place in line? walking past epitaphs, it was also interesting to think about how we treated the dead. some cultures preferred leaving the dead on mountain tops, others used human remains to make jewellery. some were buried at sea, others donated to medical research.

we couldn’t even reach a consensus on how we personified death. hindu scripture had yama riding a black buffalo and carrying a lasso. the greek portrayed death either as a bearded man with wings, or a young boy called thanatos. in lithuania, death was giltinė, an ugly old woman with a blue nose. even swedish director ingmar bergman chipped in with his idea of what death looked like in 1957’s the seventh seal.

it all seemed like an awful fuss for what was simply the fact of life ceasing to be.eventually, putting aside thoughts of ending up below ground, i simply walked among those who had gone before me.

cimetière du père-lachaise

at 118 acres, this was the largest cemetery in the city of paris. it also held the dubious honour of being the world’s most-visited. thousands of visitors strolled through each year — some to pay tribute to famous folk, others presumably to figure out what the hype was about. i slotted myself somewhere in between.

established by napoleon i in 1804, the cemetery received its name from père françois de la chaise, confessor to louis xiv who once lived on the hillside. its distance from the heart of paris was explained by the fact that cemeteries inside the city had been banned as health hazards. considering it wasn’t a very ‘popular’ choice when it first opened, père lachaise went on to flourish. after administrators transferred the remains of poet jean de la fontaine and playwright molière here in 1804, others began clamouring for space alongside. from a few dozen to the 300,000 buried today — excluding remains in the columbarium, of those cremated — this was solid proof of how powerful even dead celebrities could be.

and there were a whole lot of dead celebrities, from novelist honoré de balzac to composer georges bizet. at another corner lay polish composer frédéric chopin, his heart entombed separately within a pillar at a church in warsaw. american dancer isadora duncan rested here, as did picasso’s rival amadeo modigliani. then there was french singer édith piaf, american author gertrude stein and intellectual marcel proust. even opera diva maria callas was here. her ashes had been stolen, recovered, then scattered off the coast of greece, but the empty urn still attracted the faithful.

morrison’s original headstone, a bust of the singer, was sculpted by a fan and stolen by another in 1990. to protect the grave from the overenthusiastic — like those who used to hack pieces off the headstone as souvenirs — authorities had fenced it in. as for wilde, he suffered indignities of a more bearable kind. it was tradition, apparently, for admirers to kiss his monument while wearing lipstick. the modernist angel on the tomb originally had male genitals, which were allegedly broken off and kept as a paperweight by keepers of the cemetery.

making my way out a quiet hour later, another familiar name jumped out at me. jehangir ratanji dadabhoy tata. ‘bharat ratna,’ the headstone read. i broke into a smile.

cimetière de montparnasse

created, once again, on account of the banning of cemeteries in the city centre, montparnasse cemetery in the fourteenth arrondissement came into being by the joining of three farms in 1824. like père lachaise, it attracted tourists keen on paying respects, or standing alongside, the final resting place of a large number of long-gone intellectuals and artists.

foremost among these was charles baudelaire, nineteenth century french poet and critic who, incidentally, had once been sent by his father to calcutta in the hope of reforming his wild ways. it didn’t work. as one of literature’s bad boys, the grave attracted much attention from admirers who left behind flowers or sheets of awful verse.

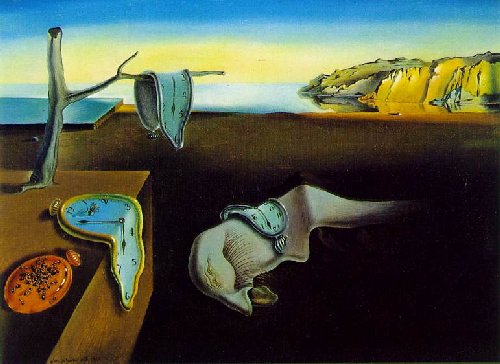

also at montparnasse lay romanian playwright eugène ionesco, the sociologist émile durkheim, writer guy de maupassant, surrealist photographer man ray and american philosopher susan sontag. and right near the main entrance were famous philosophers jean-paul sartre and simone de beauvoir, who had carried on an open relationship for years, died six years apart, and were now destined to lie alongside together.

back among the living, it occurred to me that language — no matter how inadequate — was perhaps the only way of dealing with death. the book of ecclesiastes could maintain, therefore, that there was ‘a time for every matter under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die.’ somerset maugham could describe dying thus: ‘a very dull, dreary affair. my advice to you is to have nothing whatever to do with it.’ and then there was winston churchill: ‘i am ready to meet my maker. whether my maker is prepared for the great ordeal of meeting me is another matter.’