salman rushdie is a hero!

the government of india has made it quite clear that it doesn’t want you or me to know who gibreel farishta and saladin chamcha are. the protagonists of salman rushdie’s fourth novel — you know the one, of course — have long been personae non gratae in the world’s largest democracy. it is interesting to wonder what farishta and chamcha would have to say about last month's developments in jaipur though.

rushdie was invited, asked not to come, allegedly threatened, cajoled into making an appearance via video conference and eventually told to stay away following protests by radical fundamentalists. according to reports, representatives of various organisations tried to enter the venue in protest against the video address. some of them alleged that the festival was trying to portray rushdie as a hero.

the thing is — farishta and chamcha would undoubtedly agree — salman rushdie is a hero. he can refer to himself as one primarily because he fulfils the criteria: he is a man of distinguished courage, because fighting fundamentalists for 24 years makes him one. he is a man who has performed a heroic act, because the asking of difficult questions is heroic when one lives in times that discourage questioning. he is regarded as a model or ideal, because his contribution to the arts outweighs that of many who choose to disrupt rather than debate. so, yes, salman rushdie is a hero.

this is what makes the government of rajasthan’s insistence on playing the role of mute spectator (in the presence of the world’s media, no less) such an embarrassment. it has failed on every count, kowtowing to groups of people who have arguably no idea what it is they dislike about rushdie in the first place.

in an open letter to then prime minister rajiv gandhi in 1988, rushdie wrote: ‘on october 5, the indian finance ministry announced the banning of my novel under section 11 of the indian customs act. many people around the world will find it strange that it is the finance ministry that gets to decide what indian readers may or may not read.’

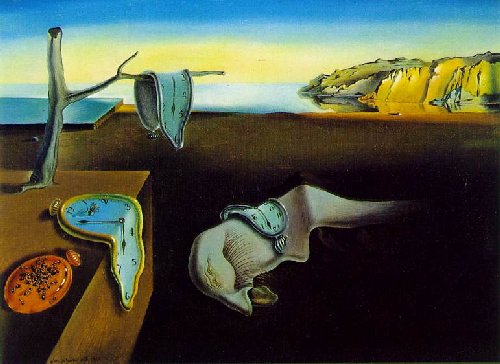

the acts of cowardice we witnessed on television through the past month were the latest in a long line of absurd developments surrounding what is, in effect, a book that a shockingly small number of indians has actually read. these developments could, ironically, find a place in any rushdie novel quite nicely. much of his writing, which falls into the genre of magic or magical realism, relies upon placing a story in a real setting while enabling its protagonists to break the rules of that world. midnight’s children, his most acclaimed work, is a meta-narrative that incorporates multiple realities, making it a perfect tool for social criticism — something that would give any writer of a much-maligned novel much to think about.

here are other pieces of information that matter: gibreel farishta and saladin chamcha, both indian muslims, are actors. the former plays hindu deities on the big screen in india, while the latter earns a living doing voiceovers in england. everything about the novel they reside in — from the controversial dream sequences to the studies in disillusionment and schizophrenia — tries to make sense of what it is like to be an alien in a strange land. it examines the notion of identity, of trying to fit into a culture different from one’s own. that the book was attacked by some of those for whom the writer was actually writing makes for an ironic footnote in its dark and colourful history.

if the past is anything to go by, this issue may not find any sort of resolution soon. this means rushdie may not address us again. the loss is undoubtedly ours.

what i would like to know is whether or not the government of india allows its citizens to read a banned book. responses to that question are vague. until i do receive an answer though, i intend to read the satanic verses again. i intend to do this because i don’t see why any democracy should dictate what i can and cannot read. i have a mind of my own. if you have one too, i suggest you do the same.